The History of an Idea

How the 2013 9-string Fanned Fret Prototype design evolved, and the design flaws which were revealed in the build.

The history of extended range guitars and lutes since the 1500s is on the

ERG Gallery page.

Site Map

Contents:

- The Virtual 12-string:

- 2012: Two New Seven String Guitars

- Transitions from one tuning system to another:

- Other Known Extended Range Guitar (ERG) designs:

- The "Brahms Guitar" of Paul Galbraith

- Fred F.'s "extreme" 10-string fanned fret

- The "Alto Guitar" and related designs:

- The Prototype 9-string Fanned Fret Harp Guitar, 2013:

- Design Flaw #1: Fingerboard Width

- Design Flaw #2: The lowest bass string was too short at 68c:

- Design Flaw #3: The highest treble string was also too short at 56c:

- A Design Success: the 12 centimeter fan width.

- Design Flaw #4: The angled bridge inhibited the vibration of the top.

The Virtual 12-string: an imaginary ERG (c 1995)

My first conception of an extended range guitar, dating from about 1995, was purely an imaginary thought tool, which I used for silent reading of piano and orchestral scores which are written far beyond the range of the six string guitar. I called it the "Virtual Twelve String". It consisted of six "real" strings, tuned E2 A2 D3 G3 B3 E4, as on a normal six string guitar, and six "virtual" (i.e., imaginary) strings, three super-trebles tuned A4, D5, G5, and three sub-basses tuned B1, F#1 and C#1. I had no idea of trying to create this instrument in physical reality at the time, but I began to think about it. It was clear that it was not a practical design, and to play it optimally would require perhaps four hands, anyway, so this design remained strictly in the realm of dreams, but it did serve as a kind of beacon for the move to the seven-strings in 2012. The 2016 Fanned Fret Harp Guitar will express three of the six "virtual" strings in physical reality. The other three will still remain imaginary... probably forever.

The Virtual 12-String - an imaginary thought tool

2012: Two New Seven String Guitars by Salvador Castillo:

Even before we moved to Mexico many long years ago, we had found ourselves in competition with other guitar duos whose arrangement techniques were usually limited to the improvised "you strum chords, I pick the melodies" type, and we early saw the potential value of more carefully worked out arrangements in which melodies, bass lines, and intermediate supporting harmonies would be as well balanced and carefully composed as in classical composition.As our duet arrangements of Mexican boleros and other popular songs began to develop in complexity and depth, we found ourselves very much up against the range limitations of the six-string guitar. In arranging for two six string guitars, the bass and the melody must often be so close together as not to leave room for the full development of the supporting parts. A greater range began to appear desirable. In guitar-based styles of Mexican traditional music, the full range of pitches is supplied by a combination of three instruments: (1) a double bass or a guitarron, (2) a guitar, and (3) a requinto, a small guitar tuned a fourth higher and with a typical scale length of around 54c (21"). We sought some way of developing a similar range of sound without sacrificing the many working arrangements which we had already made for two regular six-string guitars and which we had been performing for a number of years. At one time we also possessed a double bass and a requinto. However, we often play on small, cramped stages, and to carry a number of instruments and to manage them on stage is very inconvenient. I was never much of a bass player anyway.

In 2011 we were able to take a major step forward by ordering a pair of custom seven-string guitars from luthier Salvador Castillo of Paracho, Michoacan, Mexico. (We had been playing a pair of six-string guitars made by him since the fall of 2007, picture above right.) Salvador has made his reputation as the pre-eminent builder of Flamenco guitars in Mexico, but he also builds very lovely classical guitars and has built, for his own satisfaction, many experimental designs. He is one of the key "helpful people" in our lives. We have played his guitars in public exclusively since we bought our first pair of guitars (six strings, Palo Escrito and Cedar) from him in 2007.

Jack and Frances with the matched set of Castillo six-strings in 2007.

Tops: Western Red Cedar (Thuja Plicata). Backs and sides: Palo Escrito (Dalbergia Paloescrito). These

are the quintessence of the typical Mexican guitar type except that they are of unusually high quality.

Castillo no longer offers this model.

Jack and Frances with the matched set of Castillo six-strings in 2007.

Tops: Western Red Cedar (Thuja Plicata). Backs and sides: Palo Escrito (Dalbergia Paloescrito). These

are the quintessence of the typical Mexican guitar type except that they are of unusually high quality.

Castillo no longer offers this model.

Jack and Frances with the 7-string guitars built by Castillo in 2012. Tops: Spruce (Picea Abies). Back and sides: Granadillo (Platymiscium Yucatanum).

Transitions from one tuning system to another:

Some may be curious how a professional player can transition from one instrument type to another without taking a year off to practice. We were able to transition from the 2007 six-string guitars to the 2012 guitars in only a little over a month because the seven strings retained the tuning we already knew for six of the seven strings. Retaining the core tuning of the guitar meant that the repertory could be transported intact, the first task being only to learn to ignore the seventh string and play as usual. I did some experiments with different tunings on the 2013 prototype 9-string guitar (because there are many possible tunings one might try) and concluded that I could not afford time required for the learning curve to port my repertory to an entirely new tuning.Other Known Extended Range Guitar (ERG) designs:

The "Brahms Guitar" of Paul Galbraith

On the one hand, we have the fanned fret eight string design invented by Paul Galbraith, shown at right. (This was considered radical at first, in the classical guitar world, but the demand for this design has grown to the point of now The Brahms Guitar type - an 8-string fanned fret design with a relatively gentle fan.

The Brahms Guitar type - an 8-string fanned fret design with a relatively gentle fan.

On the instrument below you can see a further innovation by Galbraith, a cello-style endpin which rests on a resonator box and requires a cello-style sitting position.

The width of the fan in Galbraith's design is typically only 3.5 centimeters (1-3/8"), fairly conservative. The usual tuning is B1 E2 A2 D3 G3 B3 E4 A4, but it may also be tuned A1 D2 G2 C3 F3 A3 D4 G4. It is a proven design by all accounts and could have been an option for me if I had not become greedy for yet another bass string. (I already have the low bass string B1 on my seven string, the same as the lowest string on the Brahms guitar, and I also have this string on the 2013 Prototype; for me the Brahms guitar design is a step backwards.)

The "Alto Guitar" and related designs:

The other broad design category usually, not always, has a shorter scale length for the upper strings and any number of added bass strings which are longer and usually unfretted, and require a structural extension of the neck.

The Dresden Guitar duplicates the tuning (and hence the repertory) of the Baroque lute as tuned and played by the 18th century lutenist Silvius Leopold Weiss, and is designed for specialists in that music.

This type of design has two fundamental musical problems:

- The long unfretted bass strings, usually tuned to a diatonic scale such as D2 C2 B1 A1 G1, or some such pattern, produce continual sympathetic vibrations and must be continually damped by the player. This is a great nuisance.

- They do not have a full set of chromatic bass notes. They are best suited to static, long held bass notes under unchanging harmonies in only the common keys, and are not at all suited to the kind of dynamically moving bass lines that we use in our arrangements. For these reasons, I rejected this type of design and went with the fanned fret design instead.

An 11-string Alto Guitar. The seven strings on the main fingerboard are about 58c, and the four bass strings are of graduated lengths, the longest probably about 65c (guessing by the fret layout). This is a nice variation on the Baroque lute type, and the basses are frettable, a distinct improvement for that reason over the Italian harp guitar design, but suffering still from over-resonant basses which will need continuous damping. This is a very popular design for ERGs and has many devotees. It does not suit my purpose because there is not enough length in the bass strings; the longest bass string (probably tuned A1) is shorter by 7 centimeters or so than my proposed low F#1 string and will suffer from being too thick to be useful as a dynamic string, just as on my 2013 prototype. These low basses, being tuned diatonically, are mostly used open. The fingering to get the lowest chromatic notes in the extreme bass range is extremely irregular and inconvenient, not to say peculiar, because of the graduated fingerboard extensions.

Fred Fernseher's "extreme" 10-string fanned fret, built around 2010 (?)

Despite the sketchy information available, this is a very important instrument for this project because it is the only other instrument that I know of (yet) in the world which could be considered a prototype for my design. A gentleman named Fred Fernseher from Texas had built for him, a few years ago, a ten-string fanned fret classical guitar with dimensions very similar to my prototype of 2013, which is the only other nylon-strung acoustic (classical type) instrument with an extreme fanned-fret design like mine that has been publicized on the internet.

Fred and I are very different musicians, and we have made some different design choices, which is not at all surprising to me, considering how many design options I have considered myself. The amazing thing is that our prototypical designs, arrived at completely independently, were so similar. Fred's design, with ten strings, was even more audaciously ambitious than mine, and while I have complete sympathy with his design choices and feel that I understand the reasoning behind them, my own 9-string design is in fact slightly more conservative.

For instance, Fred put the "perpendicular fret" at the midpoint, the 12th fret, resulting in a very extreme angle for the first position frets. This design choice makes it easier for the luthier and harder for the player: the more extreme the angle of the bridge, the more the internal structure of the top must be redesigned; the more extreme the angle of the nut, the harder it is to play in the lower positions. This particular issue has been explored at length on the sevenstring.org ERG forum from the player's point of view, the consensus being that the "perpendicular" fret should be at around the seventh fret for most players. Salvador Castillo has explained to me the luthier's point of view, which is that the closer the angle of the bridge to the normal position, the more predictable the performance of the top with conventional bracing patterns. Any radical design which involves re-envisioning the internal structure of the guitar must be perfected over time by constructing a number of instruments, and it is impossible to guarantee such a design straight out of the box on the first try.

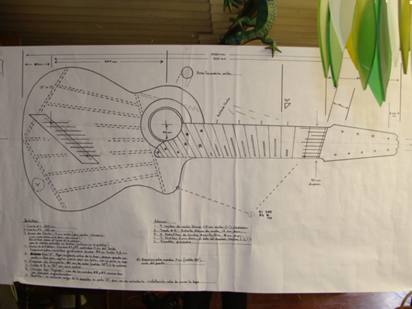

I chose to place the "perpendicular fret" at the 5th fret on my 2013 Prototype (as opposed to the usual 7th fret on the "Brahms Guitar") and have placed it at the 3rd fret in the new design for the 2016 9-String Fanned Fret Harp Guitar, making first position more comfortable and transferring most of the extreme angle to the bridge end where it becomes an issue of the internal design of the guitar rather than an issue of left hand technique. This is why the soundhole is in a different position on the plan for the 2016 9-string build, to allow more vibrating area on the top, which is somewhat constrained by the angled bridge.

In critiquing Fred's design, I note that his low E1 string at 68c is tuned a whole step below the lowest string on my 2013 Prototype, which has the same length. As I found my low F# to be unsatisfactory, I should expect his low E1 to be worse. However, Fred made a comment in one of his posts to the effect that he expected to use the low basses only as open strings, which indicates that he was not looking for the same results that I was. His low E1 probably sounds wonderful when played open, and might also sound wonderful when fretted provided only one note is played at a time. However, as I discovered with my 2013 Prototype, and as discussed further below, such a string does not perform well when fretted rapidly, and it is precisely this kind of dynamic bass line that I wish to be able to play, instead of the long-held, static bass notes of the 19th-century harp-guitar style. In other words, I want to be able to "play bass" on this instrument, rather than just occasionally playing one single deep bass note and letting it ring.

Issues with very high-pitched nylon or fluorocarbon strings:

A final commentary on Fred's design has to do with the high C5 string, at 54c. I have never played Fred's guitar, so I have no direct experience with it and can only really report on my related experiments. The reader's question might be, "Jack, how come you don't also want a high C5 string?" If such a string were to perform very well, of course I would want it. However, to conform with the tuning pattern that I would prefer, it would need to be a whole step higher yet, at D5, and besides, my own experiments with nylon or fluorocarbon strings in this range tested on an unfretted monochord device indicated that they would be of very marginal quality. It's worth noting that small instruments with open strings in this pitch range, specifically the mandolin and the violin, typically use steel strings for their A4 and E5.Edit 2018: When we were playing Castillo's cedar-topped six-strings, we were playing un-amplified for a couple of years, and fluorocarbon strings gave us a little more punch and projection. When we first got the seven strings, we found that they (being new spruce tops) were not as loud as the cedar tops, and so we began to use external piezo pickups and a sound system again (there could be a whole page about our adventures with sound systems and the quantities of money we have spent on gear that turned out to be not quite right). However, we kept using fluorocarbon strings for a couple of years before we switched back to nylon.

On the 2013 prototype, I used a Seaguar Red Label (that's a brand of fishing line) fluorocarbon string with diameter .47mm (.019"). This is thicker than I had originally calculated. Seaguar fluorocarbon at .40mm works, but lacks punch. (I bought a roll of .43mm fluoro fishing line of a different brand to try, and it was too irregular for guitar strings. I will buy Seaguar brand again in the future; it is made to superior tolerances.)

However, on the newer 2016 build I am using rectified nylon again. The additional volume of fluorocarbon is not necessary when playing amplified, and nylon is sweeter. Currently I have a .022" high A string, D'Addario brand. At Strings by Mail dot com they have a "specialty singles" dept. where they offer strings in hundredth of an inch increments, mostly by D'Addario and La Bella, but I prefer D'Addario's rectified nylon.

A nylon .022" also worked on the 2013 prototype for the high A, but the fluorocarbon had more punch and at that time that was still a priority, perhaps because that instrument was never quite as alive as the 2016 build. I used to prefer fluorocarbon for its tuning stability - it doesn't fluctuate with small temperature changes (like somebody opening a door) in the way that nylon does, and also, fluorocarbon being a little brighter than nylon compensates for the fact that I don't play with nails any more. Fluorocarbon is also stronger, and will stretch to a far higher tension than nylon, which helped give my 2013 Prototype a little more punch in the high end. But everything changes. We are playing with a lot less physical force than ten years ago when we played unamplified.

For my purposes, to achieve a superior result with only 9 strings would be better than a marginal result with 10 strings. Based on my experience with my 2013 prototype, I am deep enough in the weeds already, and with the 2016 build I fully intend to have a guitar built that I can perform on, and not merely the results of another experiment. (This has proved out: the new build is definitely a performance instrument and not an experiment.)

The bottom line is that Fred's 10-string fanned fret model, even though I never laid hands on it, gave a good deal of information indicating (at least) that my own design was not as radical as it could be, which was somewhat reassuring to me in the uncertainties of the design process.

Enter the Prototype 9-string Fanned Fret Harp Guitar, 2013:

In the spring of 2013, I made drawings of many possible versions of the Prototype, stretching the important variables of string length and fingerboard width in as many different ways as I considered practical. About June I threw up my hands and said, if I don't get one of these built I'm just shooting in the dark. At this point I could not see the forest for the trees, but I picked what I thought might be the most likely design, took it to Paracho and asked Salvador Castillo to build it. The design that I picked actually was intended to answer a number of questions about how extreme some of the parameters could be: it had a too-narrow fingerboard (I won't make that mistake again) and an extremely wide fan (which works fine). Castillo was rightly skeptical but built it exactly as I asked. It is a beautiful instrument in spite of the design flaws which became apparent. My preconceptions and the extreme parameters chosen were responsible for several design flaws and one (in retrospect) silly mistake, but these had to be proven by being translated into physical reality in order to become apparent. It is hard to imagine how this step could have been avoided, regardless of what initial design I had chosen. Only after carefully studying the flawed design for over two years have I been able to project correct solutions to the design issues.Design Flaw #1: The Fingerboard at 69mm was too narrow after all

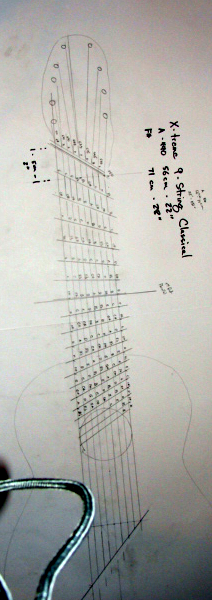

As I discovered, there are many guitarists playing electric fanned fret instruments. A wide variety may be seen on the "ERG" forum at sevenstring.org. These instruments often have very narrow string spacings, 7mm or less at the left hand end, and by this I was misled. The typical left-hand-end string spacing for classical guitars is minimum 8mm and more often 8.5mm or 9mm. However, This (unused) prototype drawing featured a 15 centimeter fan, which I decided was probably too extreme, and not

necessary to achieve the results I wanted.

This (unused) prototype drawing featured a 15 centimeter fan, which I decided was probably too extreme, and not

necessary to achieve the results I wanted.Note that the "perpendicular" fret is at #7, and that the nut is at such an extreme angle that it will be very hard to make a barre in first position (the F Major chord for instance. Even on the actual 2013 Prototype this is difficult.)

I made many such drawings to test various configurations, and some of them I cut out and pasted onto cardboard mockups.

The appropriate string spacing, (as I have now determined for myself), is 9mm, and the appropriate fingerboard width for 9 strings is therefore around 80mm, leaving 4mm at each edge so the string doesn't slip off the fingerboard (8 spaces x 9mm = 72mm plus space at edge). I like four millimeters at the edge of the fingerboard. I understand that some people might consider 9mm a little bit wide, and might be inclined to cheat the string spacing down to 8.5 or 8mm. However, the lowest bass strings are fatter than a normal low E string, and they need more space between them, and also, the left hand is reaching the opposite side of the fingerboard (that is, the bass side) at something of an angle, and the extra spacing helps a lot to play cleanly on the bass strings.

My 2013 Prototype finished and sitting on Castillo's work bench.

I proved, through long hours of practice in 2013 and 2014, that it was indeed possible for me to learn to play on the narrow string spacing.

However, a completely unforeseen problem arose.

I proved, through long hours of practice in 2013 and 2014, that it was indeed possible for me to learn to play on the narrow string spacing.

However, a completely unforeseen problem arose.Along with the narrow spacing of 7.5mm between strings at the left-hand end, I had placed the right-hand end string spacing at only 10.5mm, rather than the usual 11.5mm, for the same reason, that I thought the wide span might be unmanageable. This again was an error, as it turned out, although some other guitarist might have found it workable. The reason is that I now play without nails on my right hand, and therefore have substantial callouses on my right hand fingertips as well as those of the left hand. The narrow string spacing requires a slightly different angle of attack, and therefore the callouses develop differently. When I tried to spend several days practicing the Prototype, and then went to perform with Frances on the weekend using the seven-string with its different spacing, I developed blisters on my right-hand fingertips. This problem would not go away unless I transitioned completely to the Prototype, which simply was not possible for me at that time, since I had not yet modified it to an 8-string (the ultimately workable solution), and in any case the narrower spacing turned out not to be any advantage. In any event, I proved (for myself) that the wider string spacings at both ends of the strings were preferable, and this information has gone into the new design proposed for 2016.

Design Flaw #2: The lowest bass string was too short at 68c:

I had calculated this one carefully. First of all, the standard lengths for guitars are "short scale" at between 62 and 64 centimeters, "standard scale" at 65c, and "long scale" at 66c. I had previously experienced "long scale" classical guitars as hard to play, and this was a limiting preconception causing me to think that 68c (the length that I actually chose for the longest string of the 2013 Prototype) would be very long indeed and that anything longer yet would be completely unmanageable. I have changed my mind about this after playing the Prototype. It turns out that the functional scale length of a fanned fret guitar is the average length of the strings, not the length of the longest string. The average string length of the 2013 Prototype is 62 centimeters ( (56c + 68 c) /2 ) which feels quite short indeed under the hand. The average string length on the new 2016 build will be 66 centimeters ( (60c + 72c) /2 ) and I expect this to be manageable based on my experience with the prototype.A standard "short scale" electric bass guitar has a string length of 30", or about 76c. The lowest string being E1, the second fret on that string is F#1, my desired pitch for the lowest string of the fanned fret 9-string. Using the "rule of 18" (nowadays refined to 17.817152) I calculated the second fret of a short scale bass to measure 26-3/4", or 678.86mm, from the bridge. So I initially believed that 680mm, or 68c, should work well for my low F# string. The advice I had from electric fanned-fret guitar players on the sevenstring.org forum concurred with this in general. Although none of the guitarists who posted there had yet tried a classical-guitar type design with a low F#1 at this length, there was one player who had had built an electric solid-body guitar with nylon strings (and a piezo pickup) with the lowest string at 68c, and he was apparently not unhappy with it at that time. Later he announced plans to build another with a longer lowest bass string, either 70 or 72c, but that was after my 2013 prototype had already been built. So apparently we duplicated the error.

Electric basses use flat-wound strings. On a classical guitar with round-wound strings, a low F# at length 68c is quite thick; I used a .074" (about 1.6mm) diameter string. Although I had tested the string on a monochord testing device I had made, I could not test it on actual frets until the prototype had been built, and then I found that the low F# string at 68c actually made an unpleasant clicking sound against the frets when moving from one note to the next, and so, in spite of the fact that the open string alone sounded totally profound, the string was unusable as planned. A thicker string was even more unsatisfactory in this respect, and also the increased tension created a bizarre and inexplicable rattling noise in the low frequencies, a possible unforseen flaw in the internal body design but extremely difficult to diagnose and probably impossible to fix. (The internal structure was redesigned for the 2016 build, and this particular problem did not recur.) A thinner string just sounded like a wet noodle and had no resonance. So the bottom line is that I didn't get my desired low pitch of F#1 at the length of 68c. My revised length for the 2016 build was 72c (28-3/8") for the low F# string. I also considered 70c, but as a matter of intuitive guesswork based on experience so far, as well as on experiences reported by electric guitarists at the sevenstring.org ERG forum, I didn't think that that 70c would be quite long enough. You might ask, "Wouldn't it have been wiser to build another prototype first?" Yes - if I had unlimited time and funds. I could see spending 50 grand on prototypes. That would really answer some questions. However, I worked with the information I could get from the 2013 prototype, and as it turned out the new build of 2016 is much better sounding and more playable; as of late 2018 I have played it for almost three years straight, and while I did go through a period in late 2016 and 2017 of elbow, shoulder and wrist pain, which slowed me down for a while, I believe that I have turned the corner on that, knock on wood, and I play no other guitars.

To continue with the explanation: a "medium scale" electric bass has a string length of 32", or 813mm. The second fret is 724mm, equal to my proposed F# string for the 2016 build. As electric basses are also made in 34" (864mm) and 35" (889mm) string lengths, and the second frets of these longer basses are respectively 770mm and 790mm, my 720mm is still on the short side for that F#1 pitch. However, I consider these longer lengths to be too long to permit the fanned fret design to also include my desired high A4 string without what I still believe to be an unacceptably wide fan. (This is still unproven. Again, only a series of prototypes would answer these questions.)

These first two design flaws were serious enough to cause me to decide, in the summer of 2015, to remove the low F# string of the 2013 Prototype entirely and reconfigure the guitar as an 8-string with a more comfortable string spacing. I did this myself, building a modified bone saddle and nut. (The saddle has notches in it to establish a different string spacing without having to drill a new series of holes in the bridge, which appeared a daunting job although I thought about how it might be done without removing the bridge. A luthier would just replace the bridge - too much work for my limited luthiery skills.) Letting go of the low F# string was a rather bitter disappointment, as I had already created a number of solo compositions incorporating it. (These have now been revived on the 2016 9-String Fanned Fret Harp Guitar.)

Design Flaw #3: The highest treble string was also too short at 56c:

The Mexican requinto, a small guitar tuned with the highest string either at G4 or A4, usually measures around 54c (21-1/4"), sometimes 56c (22"). The Brahms Guitar, on the other hand, has a high A4 string that measures 61.5c (24"). The standard complaint from the players of Brahms Guitars is that the top string is thin and weak, because it must be very thin. However, from one source I read that Paul Galbraith was using a nylon high A string at .029 inches. This is thicker than my E4 string, which is only .028. I have been happier in the long run with smaller gauge strings on the 2016 build, which is louder than the Prototype was anyway. It really was technically necessary to move to lighter gauge strings, because I had trouble with my left hand barre muscle in the first year of playing the new build.On the Prototype I originally hoped to be able to use a thicker string at 56c and thus to obtain a more robust sound - this of course was only speculation. As it turned out, there is no advantage - the variables of string thickness and tensile strength are converging at this pitch. The length for the high A4 string on the 2016 build is 60c, not quite as long as the Brahms guitar. This is long enough to allow the low F# at 72c without increasing the width of the fan, which on the 2013 Prototype amounts to 12 centimeters, a dimension which I have found satisfactory and workable, and which I used again in the new 2016 build.

Regardless of design variables, a string tuned to A4 has a very different quality from the E4 of a standard classical guitar, and this will not change. The A4 string at its worst could be called "twangy" or shrill; at best you can say that it has an elegant and lutelike sound but lacks the earthy and sensuous quality of the classical guitar. This is true also of Frances's 7-string with its A4 at 58c. This is something that I have cheerfully accepted with the 2013 Prototype, and which players of the Brahms Guitar design have also had to either accept or go back to an instrument without an A4.

Lowering the top string to G4, and the use of the Dowland tuning

C2 D2 F2 G2 C3 F3 A3 D4 G4or something similar, could be a good solution IF a player were developing a new repertory from the ground up. This could only be done by a much younger player than myself. I am in my seventh decade, and while I am optimistic about having enough productive time in my life to master the new 9-string design, I just don't think that I have enough time to develop a new repertory constructed entirely with a new tuning, and must leave that path for some younger player. (No doubt in a few years some kid with huge hands will make a big splash with this type of instrument.) All through this design process I have been aware of an absolute personal necessity to make sure that my legacy repertory is performable on the new instrument by keeping the original six-string guitar core tuning intact.

(In this respect the new 2016 9-String Fanned Fret Harp Guitar is more satisfactory than was the 2013 prototype, thanks to the cutaway and to the revised fan dimensions.)

A Design Success: the 12 centimeter fan width.

As mentioned, the Brahms guitar has a fan width of only 35mm, or 1-3/8". (This is very conservative, and the player will have little difficulty adapting to this minimal fan. In fact, the fanned frets are NOT the most difficult thing to deal with in such a guitar. The task of learning and integrating the notes in the new registers on the additional strings is far more difficult, and the difficulty is ONLY in what's going on in that gray area between the ears, not with the fingers. The mental challenge is far more than the physical challenge. This is an important point to emphasize to anyone who is considering taking up an extended range guitar. If you're not up for the mental challenge, don't get into it.)Various electric players are using fans up to 15c, or 6", the largest fan that I drew in my long series of experimental drawings, and the typical comment on the sevenstring.org ERG forum is that a 3" fan (76mm) is completely maneageable and routine. After drawing many different fan configurations and cutting them out and pasting them onto cardboard mockups, I concluded that the 4-3/4" (12c) fan which I actually used on the 2013 prototype would be playable, and in this I was correct.

The one distinct difficulty with the fanned frets is that because the frets are both slanted and close together in the upper registers, fingerings that are convenient on the straight-fret guitar must sometimes be changed. It is not that they are impossible, merely that they must be somewhat reconfigured. Passages that were above the 12 fret on my 7-string were particularly difficult and remain so. The logical solution, besides reconfiguring the fingerings, is to move these passages onto the next set of strings, using the high A4 string, and so passages that were above the 12th fret will now be only above the 7th fret. However, making these changes requires months of work. As matters stand, I have chosen to keep the original fingerings on as many passages as possible, and only to change them as necessary, and it was with this approach that I performed on the 2013 prototype in its later configuration as an 8-string.

Update after receiving new 2016 Nine-String:

The 2016 Nine String Fanned Fret Harp Guitar turns out to perform much better than the 2013 Prototype, such that almost all 6-string repertory that does not go above the 12th fret can be played exactly as on the six-string. With the Prototype, the limit was at about the 9th fret, for two reasons: (1) some passages were out of tune and played in tune better when moved to the next string set, and (2) the lack of a cutaway and the combination of angled frets and narrow fret spacing made many passages difficult which would have been routine on the upper frets of the six-string. With the 2016 build, the cutaway creates one new avenue of freedom, and also the instrument plays in better tune much farther up the neck than on the prototype (I spent considerable time compensating the saddle, built several different saddles for this and widened the saddle slot to 4mm to allow more compensation of the G string; and also partly compensated the nut), and lastly the fret spacing is wider on the higher frets on the 2016 build than on the 2013 prototype. Some passages, however, become difficult because of the angled frets and either require different fingerings ("cross fingerings" in the left hand) or need to be moved to the next string set.

Another workable Pythagorean ratio, 4:5, would result from a fan 60c to 75c. In my design process, I assumed that 75c would be far too long to be practical, but I am no longer sure of this after playing the 2016 build.

Another update after receiving the new 2016 Nine-String:

The new build is very comfortable to play. The placing of the right-angle fret at Fret #3 was a very good move. As noted elsewhere, the "feel" of the guitar is not that of a long-scale: the average length of all strings is only 66c, and it does not feel at all like a 660 scale guitar. The 72c low F#1 is decent enough, and demonstrates two things: that 70c would have been too short! and that 75c could be a reasonable option for a future build. Although I may well rest on my laurels and play the new 2016 Nine String for the rest of my life, IF IF IF I were to have another one built, I would consider a 15 centimeter fan from 60c to 75c, again with the right angle fret at #3. 60:75 reduces to 4:5, the next neat Pythagorean ratio (if this matters!). I rejected this design as "too extreme" in my planning stage, but now that it is clear that the 60:72 build is not at all too extreme, the 60:75 plan is once again up for consideration in the future.

Design Flaw #4: The extreme angled bridge inhibits the vibration of the top.

Basically, the 2013 Prototype design took the angled frets and bridge and plunked them down on top of a conventionally designed fan-braced top. There was no reason to suppose that any more radical internal design was necessary - it was a case of "Let's see how it works." As it turned out, the sound was a little bit dry, compared to the other Castillo instruments that we have. When the instrument was brand new, it was difficult to say whether the spruce top would develop in such a way as to alleviate this. In fact, the sound has indeed developed considerably, but the sound is still not equal to that of our 7-string guitars of 2012. This is not unexpected, after all, for a radically experimental design.The solution, for the 2016 build, was to provide a larger area of vibrating top between the bridge and the fingerboard, by (1) displacing the soundhole up into the upper bout, and (2) moving the transverse bar closer to the fingerboard. Also, the lowest bass string meets the body at its eleventh fret, rather than at the twelfth as is usual, and this means that the long stretch of the left arm to reach first position will be a little less, and that the bridge is moved farther back into the lower bout than on the 2013 Prototype. I actually made one drawing with the neck meeting the body at the tenth fret; Castillo didn't like the bridge being that much closer to the lower bout, and talked me out of it. To some extent this has all been guesswork that must be done. While there have been untold thousands of six-string classical and flamenco guitars built, and the six string design may be considered to have been perfected through long experience, this new design may not be perfected for another generation. But the quality of the 2016 build is far better than the Prototype, and it has not required building a dozen prototypes to achieve this.

Update after receiving the new 2106 Nine String Fanned Fret Harp Guitar:

The sound of the new build has none of the flaws and quirks of the 2013 Prototype. It has a lovely, smooth, rich, sound from top to bottom, and in particular the transition from the E4 string to the A4 string is smooth and even. The A4 string does not seem to be stronger than on the other A4 instruments we have, but it is sweeter. There is, however, no noticeable tonal jump between the E4 and A4 strings except in first position, where the A4 is noticeably brighter as might be expected.

Similarly with the basses: very smooth transitions between strings and even-ness of tone. There was one minor deficiency to be observed which has steadily diminished since the instrument was brand new. (This is still a brand-new spruce top which has not yet developed its potential.) The apparent deficiency was that the very lowest notes, F#1, G1 and G#1, seemed slightly lacking in definition, although the notes from A1 up on the lowest string are the equal of those on the higher strings. These low notes have already opened up considerably and I hope that they will open up further in time. Even later edit 2018: widening the saddle to 4mm and putting in a fatter bone improved the bass tone quite a bit.

There is a complicating related issue at work, which is that common PA equipment typically goes down only to about 50 HZ, and those low notes F1 and G1 are precisely those which fall just below the cut-off. It is also possible that this is an indication that a longer F# is indicated: 74 or 75 centimeters. Certainly I don't think that 70 centimeters would have been satisfactory. Then there is also the "Helmholtz Resonator" factor, which is typically reinforced by tap tuning by luthiers, which appears to favor the A1 and thereby make the lower tones seem weaker.

Another question which the new 2016 build has raised: Should the amplifier include a crossover and subwoofer, or a secondary feed to a bass amp? But electronics are another topic.

Edit 2018: The basses sound fine through a regular PA system and there is no need for a bass amp, which I think would be overkill in the venues we play.

back to top

Internal bracing details of the 2013 Prototype. The end of the graphite bridge plate is very close to the transverse bar, which I believe inhibits the free vibration of the top and cuts the sustain and some of the important frequencies.

This concept drawing suggested a possible different relationship of the angled bridge to the internal bracing of the top, for the 2016 build. Note the wide expanse of freely vibrating top between the bridge and the transverse bar. Although the end of the lowest bass string is quite near to the other transverse brace on the bass side of the lower bout, the bass frequencies coming from that string are much longer wavelengths, and will probably shake the whole guitar, whereas the short-wave high frequencies on the treble side, weaker in amplitude because of the shorter and less massive strings, will be transmitted directly to the middle of the top just as in a conventional straight-fret design. (This explanation is open to criticism. In fact, Salvador, the luthier, talked me out of it; he didn't think it was a good idea.)

Here is the lattice brace (photo of actual build in process) of the 2016 Nine String Fanned Fret Harp Guitar. Castillo switched to a lattice brace design in order to distribute the vibration of the angled bridge more evenly.